Eurasian erosion

AS the Ukraine war drags on and Russia continues its aggressive behavior, not all of the former Soviet republics are falling under Russia’s contemporary spell.

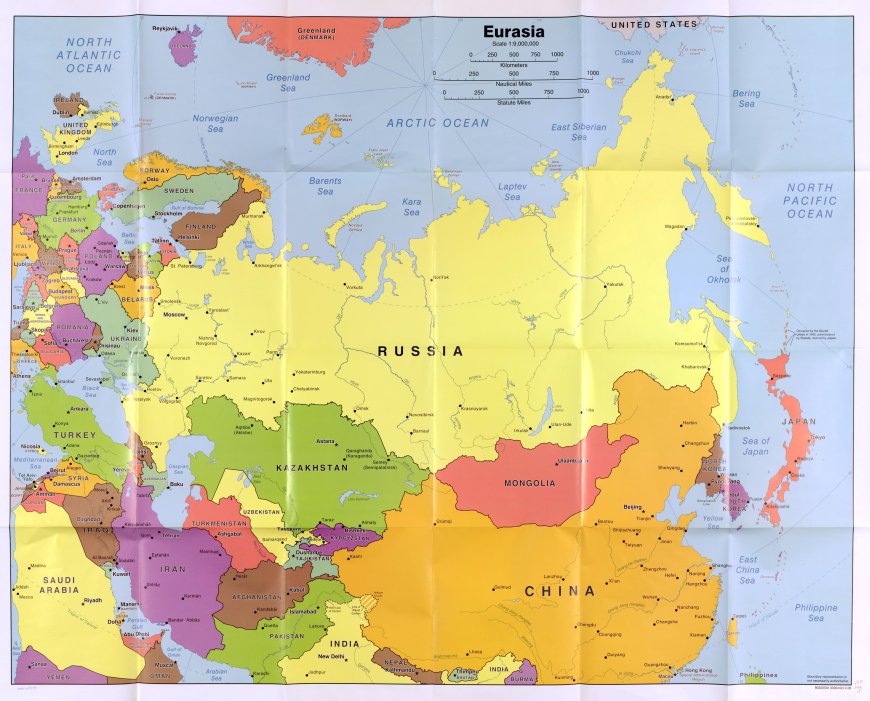

Although some countries are still attempting to balance between Moscow and other global actors operating in the post-Soviet space, several nations from Russia’s “near abroad” have already started turning their back on the Kremlin. Russia is struggling to preserve former Soviet republics in its geopolitical orbit. Nowhere is this more in evidence than in the unfolding dynamics of especially the region’s energy sector, as highlighted by recent happenings in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan.

The Second Karabakh War, fought between Russia’s ally Armenia and Turkey-backed Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020, had a serious impact on Moscow’s relations with Yerevan. Given that the Kremlin did not support Armenia’s aspirations to preserve the mountainous region under its de facto control, that round of the conflict resulted in an Azerbaijani victory.

In 2021, Yerevan accused Baku of invading parts of Armenian territory. It asked the Russian-dominated Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) for help. But Moscow once again remained silent. Armenia, naturally, began to reconsider its participation in the military alliance.

Yerevan now sees the United States and the European Union, rather than Russia, as its major partners: Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan announced on June 13 his country’s plans to leave CSTO. Such an outcome could have serious consequences for the very existence of the Russian-led organization, as sooner or later other member states begin to follow Armenia’s footsteps in reconsidering their regional partnerships, potentially even deciding to quit their membership in the CSTO.

In Kazakhstan, there are already growing demands for the country to leave not only CSTO, but also the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union. Moreover, despite being Moscow’s nominal ally, Astana is actively seeking to distance itself from the Kremlin, and to develop closer ties with the West. At the same time, Kazakhstan is aiming to strengthen trans-Caspian cooperation with Azerbaijan, hoping that such a strategy will allow Astana to increase its economic cooperation with the European Union.

It is no secret that Kazakhstan plans to increase oil exports to European countries though Azerbaijan. Presently, the Central Asian nation remains heavily dependent on the Caspian Pipeline Consortium—the route running through Russia and ending in the Russian Black Sea terminal of Novorossiysk. But Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan aim to resume pumping oil through the Baku-Supsa pipeline that has been out of service since 2022, which has the advantage of allowing Astana to effectively bypass Russia in its oil exports to Europe.

In order for this route to become fully operational, however, both Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan will have to resolve some technical issues, primarily the quality levels of the oils passing through the pipeline. Meanwhile, Astana will likely continue to rely on its fleet of small tankers taking oil across the Caspian Sea to Baku.

Given Azerbaijan’s strategic importance, as well as relatively strong Russian energy links with Baku, the Kremlin is unlikely to be able to afford to jeopardize ties with the Caspian Sea nation, regardless of Azerbaijani energy and foreign policy. Baku recently hosted three significant energy events—the 29th International Caspian Oil and Gas Exhibition, the 12th Caspian International Power and Green Energy Exhibition, and the 29th Baku Energy Forum—all of which helped Azerbaijan strengthen its energy cooperation not only with the West, but also with other countries in the Arab world. The fact that U.S. President Joe Biden sent a letter to be read at the conference, held in the Azerbaijani capital, and that Harry Kamian, senior adviser for multilateral energy diplomacy for the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Energy Resources, attended the event, perfectly illustrates that Baku is counting on Washington’s support in its plans to continue ensuring energy security in Europe.

Although no major Russian officials participated in the summits in Baku, several Russian energy companies took part in the Oil and Gas Exhibition, and Russian media actively covered the events. Such actions reveal that the Kremlin does not plan to give up easily on its energy interests in Azerbaijan, even though the former Soviet republic will continue strengthening cooperation with the EU, helping the twenty-seven-nation bloc reduce its dependance on Russian gas.

While the Kremlin’s room for political maneuvers remains limited in Azerbaijan—Turkey’s ally also having strong military ties with Israel—in Tajikistan (another Russian ally in the CSTO), Moscow’s influence seems to be relatively strong. On June 10-13, the landlocked Central Asian nation held the Dushanbe Water Process, a high-level conference on water policy and sustainable development. Russian was one of the official languages. More importantly, Ruslan Edelgeriev, Special Presidential Envoy for Climate Change of the Russian Federation, was a major guest at the conference. A prominent side event was organized by the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

The Russian Embassy to Tajikistan also participated in the Water and Glacier Festival in Dushanbe, ostensibly promoting Russian culture in the Tajik capital. On the other hand, U.S. State Department official Julien Katchinoff was a moderator and a member of the organization committee for the Dushanbe Water Process, which suggests that the Tajik authorities aimed to create a delicate balance in their multi-vector diplomacy.

Although the goal of the Tajik conference was to promote the role of water in sustainable development, it also allowed Tajikistan to strengthen energy and political ties with the European Union, given that the event was organized jointly by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in cooperation with the EU and the Tajik Ministry of Energy and Water Resources. And while Russia was not among sponsors or partners of the forum, its participation in the event indicates that for Dushanbe, unlike for some of Moscow’s other allies, distancing from Moscow is not on the agenda of the country’s foreign policy.

That, however, does not mean that the Kremlin should take Dushanbe’s loyalty simply for granted. In late April, despite Tajikistan’s CSTO membership, Virginia National Guard Soldiers conducted a mountain warfare exchange with Tajik military forces. This symbolic gesture suggests that the former Soviet republic is hardly putting all of its eggs in one basket—and that hosting a Russian military base with some 7,000 troops on its soil still does not prevent it from flirting with the United States.

But given strong Chinese influence in Tajikistan, it is Beijing, rather than Washington, that could undermine Moscow’s position in the mountainous country. In other Central Asian states where Russia has also long been a regional partner in economy, energy, and security, the West seems to be playing a far more active role. This means that in the foreseeable future, the Kremlin may have a hard time preserving its influence in the strategically important region.

One thing is for certain—if Russia suffers a defeat in Ukraine, and if it does not achieve any of its goals in the Eastern European country, most, if not all of Moscow’s allies will turn their back on the Kremlin.

By Nikola Mikovic - MAerican Purpose