There’s only one way forward after Gaza. Israelis must accept it

REFLECTING on the Gaza war and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict more broadly, former president Barack Obama offered this regret: “I look at this, and I think back, ‘What could I have done during my presidency to move this forward, as hard as I tried?’ ... But there’s a part of me that’s still saying, ‘Well, was there something else I could have done?’”

Like all presidents since Bill Clinton, Obama ran into the dreamscape of the two-state solution. Now, he is implying what Clinton learned to be untrue: that if Washington had just pushed Israel more, something markedly better could have been achieved for the Palestinians.

The United States encouraging the Israelis to do better by the Palestinians is certainly estimable and sensible. Israeli administrations really haven’t cared much about how Palestinians govern themselves so long as they don’t kill Israelis. Oct. 7 should end that disinterest.

But will the United States or Israel take the next logical step — pushing the Palestinians to move away from militant Islam and secular authoritarianism through elections that would make them directly responsible for their fate? It’s difficult to imagine either nation readily will. In particular, the Israeli allergy to Muslims voting — Arab elites have a better track record of accepting the Jewish state — might prove a serious obstacle to a more peaceful modus vivendi between Israelis and Palestinians.

But what are the alternatives?

Elections provide the only means to develop new leadership. Democracy could misfire, as it did in 2006 when Hamas won the largest slice of the last free legislative election. And any Palestinian leadership will get caught in a perverse situation: the need to cooperate with a much stronger Israel while maintaining sufficient Palestinian independence and pride. But the status quo has given Palestinians ghastly political dysfunction and devastating collisions with the Israeli military and security services.

And it has given Israelis the deadliest day for Jewish people since the Holocaust, which has empowered ever-harsher right-wing parties aiming to incorporate ever-larger swaths of the West Bank, making Israeli-Palestinian coexistence untenable.

Israeli opinion in favor of a two-state solution has been moribund since Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat refused Clinton’s entreaties in 2000 at Camp David and the second intifada commenced. The conflict’s suicide bombings and rocket attacks eviscerated the Israeli left, which had taken “risks for peace.”

The elections in 2006 and Hamas’s coup against Fatah in Gaza in 2007 further depressed Israelis. And the advancement and spread of missilery — at which Iran, Hamas’s primary arms supplier, excels — have now made it inconceivable that any Israeli government won’t maintain a protectorate over the West Bank. Oct. 7 has guaranteed that Israel will be tempted to replicate that model in Gaza.

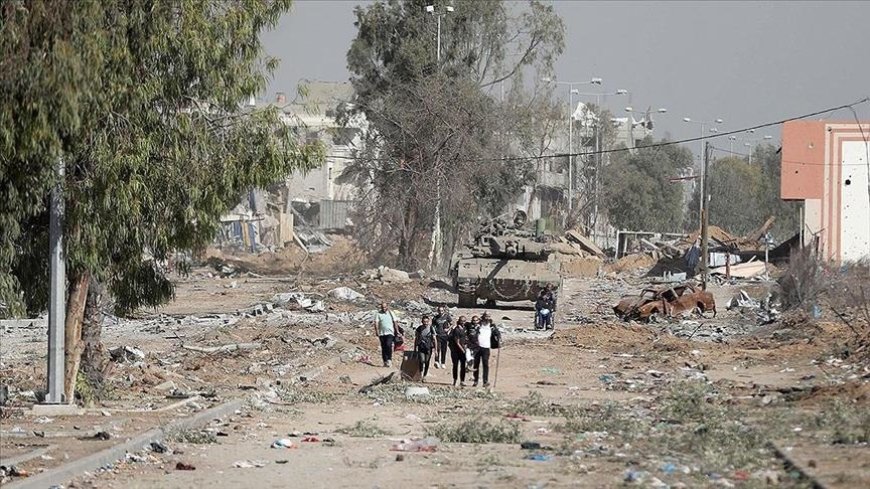

A protracted Israeli occupation therefore remains the most likely scenario, despite the fact that Israeli politicians and generals ardently want to avoid it and the Biden administration is opposed. Proximity in the modern Middle East between adversarial religious and ethnic groups routinely breeds violence. And geography and modern weaponry just don’t give Israelis and Palestinians the option of a capacious buffer zone.

Israel is probably going to replicate some form of the zoned administration that it maintains on the West Bank: Zone A is Palestinian control, Zone B is joint, and Zone C is the Israeli army only. But questions of administration, which Israel will probably have to handle mostly on its own for some time, are unavoidably tied to finding a Palestinian partner that has political legitimacy.

No one is riding to Jerusalem’s rescue to forestall an Israeli occupation. Arab states will not help out. Hamas and other radical Palestinian groups are going to have a lingering guerrilla presence in Gaza no matter how successful Israel is in killing the organization’s leadership and its paramilitary force, which is estimated to number some 40,000 men. The Europeans are not capable of stepping in. And Americans, who share a bipartisan sentiment to do less in the Middle East, aren’t likely to do so, either.

Fatah will be a continuing hindrance unless the party can prove itself at the ballot box. Better men might surface in a free vote. Fatah’s ruling elite might make a play for Gaza — a lot of money could be involved in reconstruction, and Fatah would want to preempt others who could challenge it. The separation of Gaza from the West Bank has allowed Fatah to avoid elections for 17 years.

Palestinians will surely see new elections as a means to weaken Israel’s dominion over them; they might well reembrace democracy to undermine both Israeli control and their current Palestinian overlords. Elections, which Europe and Arab states would be obliged to support (even if the Gulf monarchies might try behind the scenes to keep Fatah’s autocracy in place), could be undertaken down the road without oppressive Israeli oversight. The “international community,” rarely helpful in the Israeli-Palestinian imbroglio, could be useful on the ground with all the mechanics behind free elections.

But getting there will be difficult. Hamas, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and other explicitly holy-warrior organizations would have to be banned to satisfy Israelis. And even still, whatever the results are, Israelis are certain not to like them.

Regardless, given that there is no plausible alternative, Jerusalem should clearly state, as soon as possible, that re-enfranchising Palestinians is an essential step toward greater Palestinian autonomy. Renewed Palestinian democracy offers the possibility of a fresh beginning for everyone; nothing else does.