Rollo Romig’s book on Gauri Lankesh’s murder puts her life and death in context

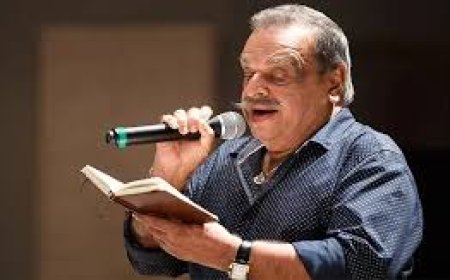

Bengaluru, with its traffic bottlenecks and Church Street lined with bookstores, is where Rollo Romig begins his account of the murder of Gauri Lankesh, a journalist who had lived most of her 55 years there, shot down at the doorstep of the home her mother had once built. The killing of Gauri, who ran a Kannada weekly and was scathing in her criticism of the ruling disposition, on a September evening in 2017, caused an uproar no one had expected. Rollo, a Detroit journalist who has been writing about south India for years, flew down in January 2018 in pursuit of Gauri’s story that would not begin or end with her. The result, a riveting book called I am on the Hit List that came out in January 2025, condenses a lot of what has been going on in the country in the past decade, and branches out to other corners in south India that Rollo found connections in, and culminates in the trial of Gauri’s murderers. About the same time that Rollo’s book came out, the last of the accused men who had been in custody was let out on bail. Seventeen of the accused have now got bail, while the 18th man is still at large. Rollo split his book into three parts, one for each period he reported in — the first two in January and July of 2018, and third in the years that followed. In the way only writers can, he brings Gauri alive in the very first page, putting her in the thick of Bengaluru traffic on the night of her murder, no less. The picture has been made unforgettable by countless reports, of Gauri stepping down from her car like she did every evening to open the gates of her house and facing the bullets fired by a strange man on a motorcycle – and ponders about the motives. Why Gauri Lankesh was assassinated: The story of an indoctrinated engineer Why Gauri? She was obviously not making a lot of friends because of the way she ran her paper — brash and outspoken, mincing no words about anyone, friend or foe, she thought unjust. But hers was a small time publication, running into no more than a few thousand subscribers at the best of times. Why would, Rollo wonders, her enemies want to pluck out a journalist who could do so little harm to them? Many said it was because she was a journalist, others thought it was due to the Lingayat connection – an influential community in Karnataka that could decide the fate of elections – that she wrote about, but the most agreed-upon theory was that she was fourth in a line of rationalists who were killed by right wing forces. Rollo, in persuasive narratives, covers all of these, with telling interviews – with the likes of late Girish Karnad, Ramachandra Guha, journalists, police, and her friends and family – meetings, and his own logical observations. Clearly, like Gauri once did, he must see little point in objective journalism. “She abandoned the cautious pose of objectivity that defined the mainstream journalism of her early career,” he writes, and quotes Gauri, “It is perhaps not possible in today’s world for a journalist to be pro-people if he is not an activist in his or her own way.”Gauri Lankesh He brings Gauri closer to the reader as he details her journalism, her writing, and even her little idiosyncrasies. She did not pretend, she did not hold grudges, she argued, and she always held space for dissent. She sounds endearing when Rollo writes how her friends would grow tired of all her arguments and would refuse to accept her friends’ requests on social media. She may have, you deduce, inherited qualities of her father P Lankesh, a journalist who had been unapologetic in his criticism even of his dearest friends. In the briefest of accounts, Rollo manages to tie them all together — the family including Lankesh and Gauri, the mother Indira who started her own business, the sister Kavitha, the filmmaker who remained closest to Gauri, and even the brother Indrajith, who once fired Gauri as editor of their father’s newspaper and appears to be sympathetic to the right wing forces that Gauri fought all along. Even her niece Esha has stories to share about Aunt Gauri in whose bedtime stories, Cinderella “was always a career woman who would never pine for a prince and who had adventured on her own terms.” These are not distractions to the main thread but personalising a woman who was killed only for proving a point, driving home a message. Sanathan Sanstha, the organisation allegedly involved in the killing of the rationalists Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare and MM Kalburgi, before they killed Gauri, features prominently in the book, with descriptions of its key players, functioning, and methods of training. Dabholkar, Pansare, Kalburgi and Gauri (clockwise from top) Parashuram Waghmare, the man who allegedly shot Gauri point blank, did not even know her till he was asked to kill her. The killers of Dabholkar or Pansare or Kalburgi may not have read their books or scholarly works or listened to their talks before pulling the trigger. All they were allegedly told was that thes

Bengaluru, with its traffic bottlenecks and Church Street lined with bookstores, is where Rollo Romig begins his account of the murder of Gauri Lankesh, a journalist who had lived most of her 55 years there, shot down at the doorstep of the home her mother had once built.

The killing of Gauri, who ran a Kannada weekly and was scathing in her criticism of the ruling disposition, on a September evening in 2017, caused an uproar no one had expected.

Rollo, a Detroit journalist who has been writing about south India for years, flew down in January 2018 in pursuit of Gauri’s story that would not begin or end with her.

The result, a riveting book called I am on the Hit List that came out in January 2025, condenses a lot of what has been going on in the country in the past decade, and branches out to other corners in south India that Rollo found connections in, and culminates in the trial of Gauri’s murderers.

About the same time that Rollo’s book came out, the last of the accused men who had been in custody was let out on bail. Seventeen of the accused have now got bail, while the 18th man is still at large.

Rollo split his book into three parts, one for each period he reported in — the first two in January and July of 2018, and third in the years that followed. In the way only writers can, he brings Gauri alive in the very first page, putting her in the thick of Bengaluru traffic on the night of her murder, no less.

The picture has been made unforgettable by countless reports, of Gauri stepping down from her car like she did every evening to open the gates of her house and facing the bullets fired by a strange man on a motorcycle – and ponders about the motives.

Why Gauri? She was obviously not making a lot of friends because of the way she ran her paper — brash and outspoken, mincing no words about anyone, friend or foe, she thought unjust. But hers was a small time publication, running into no more than a few thousand subscribers at the best of times. Why would, Rollo wonders, her enemies want to pluck out a journalist who could do so little harm to them?

Many said it was because she was a journalist, others thought it was due to the Lingayat connection – an influential community in Karnataka that could decide the fate of elections – that she wrote about, but the most agreed-upon theory was that she was fourth in a line of rationalists who were killed by right wing forces.

Rollo, in persuasive narratives, covers all of these, with telling interviews – with the likes of late Girish Karnad, Ramachandra Guha, journalists, police, and her friends and family – meetings, and his own logical observations. Clearly, like Gauri once did, he must see little point in objective journalism.

“She abandoned the cautious pose of objectivity that defined the mainstream journalism of her early career,” he writes, and quotes Gauri, “It is perhaps not possible in today’s world for a journalist to be pro-people if he is not an activist in his or her own way.”

He brings Gauri closer to the reader as he details her journalism, her writing, and even her little idiosyncrasies. She did not pretend, she did not hold grudges, she argued, and she always held space for dissent. She sounds endearing when Rollo writes how her friends would grow tired of all her arguments and would refuse to accept her friends’ requests on social media.

She may have, you deduce, inherited qualities of her father P Lankesh, a journalist who had been unapologetic in his criticism even of his dearest friends. In the briefest of accounts, Rollo manages to tie them all together — the family including Lankesh and Gauri, the mother Indira who started her own business, the sister Kavitha, the filmmaker who remained closest to Gauri, and even the brother Indrajith, who once fired Gauri as editor of their father’s newspaper and appears to be sympathetic to the right wing forces that Gauri fought all along. Even her niece Esha has stories to share about Aunt Gauri in whose bedtime stories, Cinderella “was always a career woman who would never pine for a prince and who had adventured on her own terms.”

These are not distractions to the main thread but personalising a woman who was killed only for proving a point, driving home a message. Sanathan Sanstha, the organisation allegedly involved in the killing of the rationalists Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare and MM Kalburgi, before they killed Gauri, features prominently in the book, with descriptions of its key players, functioning, and methods of training.

Parashuram Waghmare, the man who allegedly shot Gauri point blank, did not even know her till he was asked to kill her. The killers of Dabholkar or Pansare or Kalburgi may not have read their books or scholarly works or listened to their talks before pulling the trigger. All they were allegedly told was that these people were a threat to their faith. It was one speech touching on Hinduism that Gauri made in 2012 that is believed to have put her name on the list.

The list – of people marked for killing by the same forces who killed the rationalists – had been doing the rounds at the time of Gauri’s killing. Rationalist writer KS Bhagwan was meant to be on it. Perhaps Umar Khalid, the student activist who has been jailed since 2020, was too, for he narrowly missed a bullet in 2018.

Rollo’s veering off to the political climate of the country – the many, many incidents of intolerance and protests and controversial laws – seems not just natural, but necessary to make sense of Gauri’s story. Everyone from Prime Minister Narendra Modi to pawns like Waghmare fall into place.

Two sections that are not connected to Gauri’ story, feature as interludes, when the author delves into the churches of Kerala and the Saravana Bhavan crime story.

The takeaways can be many — the interludes may be welcoming to some, the investigation itself to others. As a reader, it was enticing simply to learn about Gauri, as a girl who survived food poisoning, who grew up loving PG Wodehouse, and who stayed away from regional politics, who was so adaptive to change that she picked up her mother tongue like a baby and loved it all over again, spoke and wrote and fought in it, mended her journalism, her attitudes to life, and at 55, seemed still so willing to change.

By the time the book comes to her friend Shivasundar, who attends the trial of her murderers every single day, saying that there is little else he could do for his “indispensable, incorrigible, unsalvageable, murdered friend”, you just might find a lump in your throat.

The book is published by Context, Westland Books